Still Places #9 : Designing for Peace

All Text & Images: Dom Galloway | GardenSpace (unless otherwise noted)

The act of designing a garden may seem, at first glance, to belong only to the realm of beauty and leisure. Yet in our turbulent age, it has taken on a deeper significance. To shape a garden is also to shape relationships: between people, between cultures, and between humanity and the living earth. Increasingly, gardens are being created not only as private sanctuaries but as instruments of peace—peace among communities, and greater harmony with the planet that sustains us.

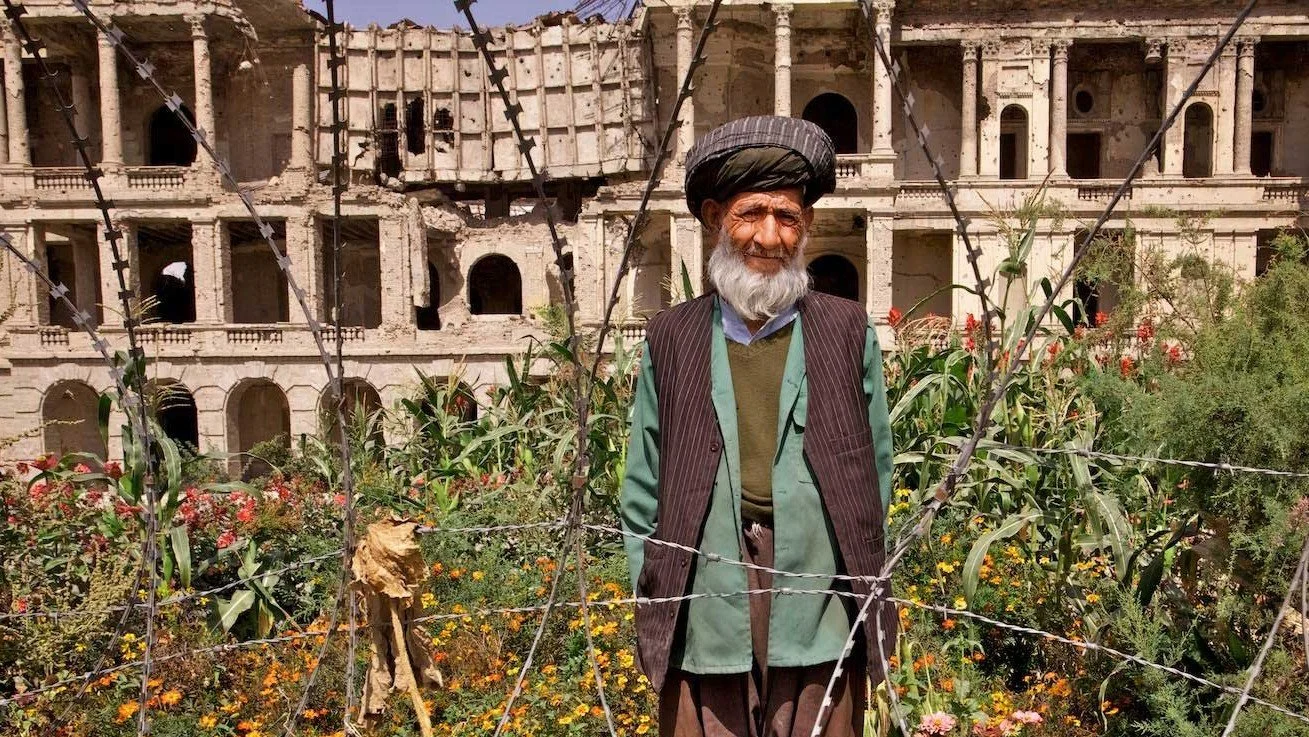

Lalage Snow ‘War Gardens’ Image Credit: Lalage Snow

The idea is not new. Across centuries, gardens have served as places of reconciliation and rest. In Japan, the temple garden has long been a space where harmony is cultivated, not only in the arrangement of stones and water but in the minds of those who enter. In Islamic traditions, the garden was conceived as an earthly reflection of paradise, a vision of balance and abundance that offered respite from the harshness of the desert world. In the aftermath of wars, memorial gardens have been planted as living tributes—green spaces where grief and remembrance can be transformed into quiet reflection rather than division.

Today, the work of designing for peace takes on fresh urgency. We live in an age marked by ecological pressures, cultural tension, and a widespread hunger for belonging. The garden offers a subtle yet powerful response. It is a medium that can embody reconciliation in its very structure. A public garden, for example, designed with sensitivity to cultural traditions, can become a place where people of diverse backgrounds encounter one another through beauty rather than conflict. Shared pathways, open spaces, and plantings that carry meaning across cultures create environments where difference is acknowledged yet held in harmony.

Peace is found through the senses. A well-considered garden can calm the body and spirit. Shaded walks, flowing water, soft plantings, and fragrant flowers all work to ease the nervous system, to slow the breath, and to invite reflection rather than agitation. In urban settings where noise and tension often dominate, such gardens are not luxuries but necessities—quiet antidotes to the pressures of modern life.

Equally vital is the ecological dimension. Gardens can no longer be designed only as human ornaments; they must also serve a wider community of life. Planting to restore pollinators, cooling urban heat through canopy trees, capturing and filtering water, and caring for our soil—these are all acts of reconciliation between humans and nature. A peaceful garden is one that does not demand domination of the earth but collaborates with it. Its beauty lies not only in form but in function, in the way it supports the flourishing of many species alongside our own.

“Many things grow in the garden that were never sown there.” - Thomas Fuller

Examples of designing for peace can be found across the world. After conflicts, memorial parks have become shared grounds for reconciliation. In cities, intercultural gardens have been established where migrant and refugee communities cultivate familiar foods, finding healing in continuity and pride in sharing traditions. Urban rewilding projects bring degraded land back to life, offering habitats for creatures and sanctuaries for humans simultaneously. Each is a testament to the garden’s capacity to mend divides—between past and present, between communities, and between humanity and nature.

This vision is powerfully embodied by the work of Global Gardens of Peace, an Australian initiative that creates gardens in communities facing hardship around the world. Their purpose is clear: to provide places of healing, belonging, and resilience where trauma and dislocation have left deep scars. From refugee settlements to impoverished neighbourhoods, they design gardens that offer dignity, beauty, and the possibility of renewal. These projects remind us that recovery is not only the concern of hospitals and clinics, but also of communities who long for stability, peace, and the chance to rebuild. Global Gardens of Peace demonstrates how a simple truth—that gardens heal—can be carried across borders and into some of the world’s most fragile places.

To design for peace, then, is to acknowledge that gardens carry moral weight. They are not neutral spaces. The choice of what to plant, how to shape, and whom to welcome carries consequences for culture and ecology alike. A peaceful garden is one designed with care, empathy, and humility—qualities our wider world is looking for.

The garden will never end wars or heal every conflict. But it can model, in living form, what peace might look like: coexistence, balance, generosity, and renewal. When we make and walk in such gardens, we glimpse not only beauty but possibility—the possibility that our shared life on this earth might be cultivated with the same patience, attentiveness, and care.

For more:

• Global Gardens of Peace, (https://globalgardensofpeace.org/ )

• Lalage Snow, ‘War Gardens’, (https://www.lalagesnow.co.uk/portraiture/ )

• Lalage Snow, ‘The Gardeners of Kabul’, (https://youtu.be/1y-DIrXUxiY?si=zp14DWpWhSz2Axoj )

• Joshua Luke Smith, ‘Sunflowers in Babylon’: (https://youtu.be/fsiB9uCMZ68?si=jumPe_Nsr2igDODW )

For help to developing and sharing your garden ideas, contact us today.